There are several ways to think about what publishing networks can be. The models range from a more traditional portfolio of owned and operated properties to loosely connected collections of self-publishing individuals.

Gawker Media is a great example of the O&O portfolio model. Nick Denton recently shared some impressive growth figures across the Gawker family of sites. In total, the network overtook the big US newspaper sites USA Today, Washington Post and LA Times. He’s looking to swim with some bigger fish:

“The newspapers are now the least of our competition. The inflated expectations of investors and executives may one day explode the Huffington Post. And Yahoo and AOL are in long-term decline. But they are all increasingly in our business.”

Gawker owns the content they publish and pays their staff and contributors for their work. The network of sites share a publishing platform but exist independently and serve separate but similar audiences: Jalopnik, Jezebel, Gizmodo, Gawker, Lifehacker and Kotaku.

This model of targeted media properties is what made Pat McGovern so successful with his privately-owned IDG, a global portfolio of 300+ computer-focused magazines and web sites with over $3B in revenue…yes, that’s $3 BILLION!

The Huffington Post has been incredibly successful using the flip-side of Gawker’s model, a decentralized contributor network in addition to a small staff who all post to one media property. Cenk Uygur, host of The Young Turks, mirrors posts from his own site to the Huffington Post web site. He can use the Huffington Post to build his reputation more broadly, and Huffington Post gets some decent coverage to offer their visitors at no cost. He’s had similar success building his brand on YouTube.

Huffington Post has been technically very experimental and innovative, and contributors seem very happy with the results they are getting by posting to the site despite some controversy about not being paid for the value of their work.

Of course, Demand Media is the new Internet publishing posterboy. There’s lots of interesting coverage about what they are up to. Personally, I’m most intrigued by the B2B play they call ‘Content Channels‘. They are getting distribution through other sites such as San Francisco Chronicle and USA Today where they provide Home Guides and Travel Tips, respectively.

Of course, Demand Media is the new Internet publishing posterboy. There’s lots of interesting coverage about what they are up to. Personally, I’m most intrigued by the B2B play they call ‘Content Channels‘. They are getting distribution through other sites such as San Francisco Chronicle and USA Today where they provide Home Guides and Travel Tips, respectively.

The business model is just a very simple advertising revenue sharing agreement. And production costs are kept to a minimum by paying very very low fees for content.

I find WordPress fascinating in this context, too.

It doesn’t make much sense thinking of WordPress.com as a cohesive network except that there’s a single platform hosting each individual blog. The individuals are not connected to each other in any meangingful way, but WordPress has the ability to instrument activities across the network.

A great example of this is when they partnered with content recommendations startup Zemanta to help WordPress bloggers find links and images to add to their posts. There are now thousands of WordPress plugins (including our News Feed plugin) that individual bloggers deploy on their own hosted versions of the platform.

It’s not exactly a self-fueling ecosystem, as there are no revenue models connecting it all together. But it may be the absence of financial shenanigans that makes the whole WordPress ecosystem so compelling to the millions of participants.

Then there’s Glam Media which combines their portfolio of owned and operated properties with a collection of totally independent publishers to create a network. In fact, it’s the independents who actually make up the lionshare of the traffic that they sell.

Glam looks more like an ad network than a more substantive source of interest, but they have done some very clever things. For example, they are developing an application network, a way for advertisers to get meaningful reach for brand experiences that are better than traditional banner ad units. If it works it will create value for everyone in the Glam ecosystem:

“As a publisher, you make money on every ad impression that appears as part of a Glam App. This includes apps embedded on your site and on pop-up pages generated by an application on your site. Glam App ad revenue is split through a three-way rev share between the publisher, app developer, and Glam.”

There’s something very powerful about enabling rich experiences to exist in a distributed way. That was the vision many people shared in terms of the widgetization of the web and a hypersyndication future for media that still needs to happen, in my mind.

At the Guardian we’re balancing a few of these different concepts, as you can see from the Science Blog Network announcement below and our fast-growing Green Network. The whole Open Platform initiative enables this kind of idea, among other things.

There are a few different aspects of the Science Blog Network announcement that are interesting, not least of which is the fact that I was able to post the article directly on my blog here in full using the Guardian’s WordPress plugin.

As Megan Garber of Niemen Journalism Lab said about it…

“The blog setup reframes the relationship between the expert and the outlet — with the Guardian itself, in this case, going from “gatekeeper†to “host.—

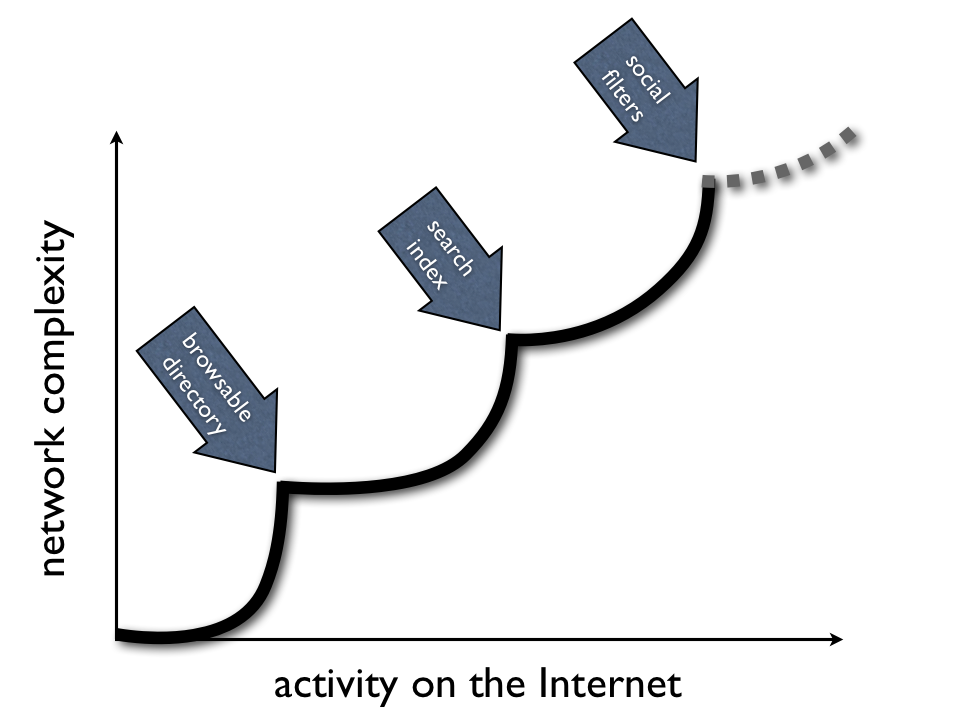

The trick that few of the publishing networks have really worked out successfully in my mind is how you surface quality. That’s a much easier problem to solve when your operation is purely owned and operated. But O&O rarely scales as successfully as an open network.

Amar Bhidé wrote a wonderful essay for the September issue of Harvard Business Review about the need for human judgment in a world of complex relationships.

“The right level of control is an elusive and moving target: Economic dynamism is best maintained by minimizing centralized control, but the very dynamism that individual initiative unleashes tends to increase the degree of control needed. And how to centralize—whether through case-by case judgment, a rule book, or a computer model—is as difficult a question as how much.”

At the end of the day it comes down to purpose.

If the intent of the network is purely for generating revenue then it will be susceptible to all kinds of maligned interests amongst participants in the network.

If on the other hand the network is able to create value that the participants actually care about (which should include commercial value in addition to many other measures of value), then the network will have a long growth path and may actually fuel itself over time if it is managed well.

The strategic choices behind the controlled versus open models are very different, and there’s no reason both can’t exist together. What will ultimately matter most is whether or not end-users find value in the nodes of the network.

This article titled “Guardian science blogs: We aim to entertain, enrage and inform” was written by Alok Jha, for theguardian.com on Tuesday 31st August 2010 12.00 UTC

This article titled “Guardian science blogs: We aim to entertain, enrage and inform” was written by Alok Jha, for theguardian.com on Tuesday 31st August 2010 12.00 UTC

It’s nearly the end of summer holidays, and there are plans afoot in the blogosphere.

You would not know it from general media coverage but, on the web, science is alive with remarkable debate. According to the Pew Research Centre, science accounts for 10% of all stories on blogs but only 1% of the stories in mainstream media coverage. (The Pew Research Centre’s Project for Excellence in Journalism looked at a year’s news coverage starting from January 2009.)

On the web, thousands of scientists, journalists, hobbyists and numerous other interested folk write about and create lively discussions around palaeontology, astronomy, viruses and other bugs, chemistry, pharmaceuticals, evolutionary biology, extraterrestrial life or bad science. For regular swimmers in this fast-flowing river of words, it can be a rewarding (and sometimes maddening) experience. For the uninitiated, it can be overwhelming.

The Guardian’s science blogs network is an attempt to bring some of the expertise and these discussions to our readers. Our four bloggers will bring you their untrammelled thoughts on the latest in evolution and ecology, politics and campaigns, skepticism (with a dollop of righteous anger) and particle physics (I’ll let them make their own introductions).

Our fifth blog will hopefully become a window onto just some of the discussions going on elsewhere. It will also host the Guardian’s first ever science blog festival – a celebration of the best writing on the web. Every day, a new blogger will take the reins and we hope it will give you a glimpse of the gems out there. If you’re a newbie, we hope the blog festival will give you dozens of new places to start reading about science. And if you’re a seasoned blog follower, we hope you’ll find something entertaining or enraging.

We start tomorrow with the supremely thoughtful Mo Costandi of Neurophilosophy. You can also look forward to posts from Ed Yong, Brian Switek, Jenny Rohn, Deborah Blum, Dorothy Bishop and Vaughan Bell among many others.

In his Hugh Cudlipp lecture in January, Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger discussed the changing relationship between writers (amateur and professional) and readers.

We are edging away from the binary sterility of the debate between mainstream media and new forms which were supposed to replace us. We feel as if we are edging towards a new world in which we bring important things to the table – editing; reporting; areas of expertise; access; a title, or brand, that people trust; ethical professional standards and an extremely large community of readers. The members of that community could not hope to aspire to anything like that audience or reach on their own; they bring us a rich diversity, specialist expertise and on the ground reporting that we couldn’t possibly hope to achieve without including them in what we do.

There is a mutualised interest here. We are reaching towards the idea of a mutualised news organisation.

We’re starting our own path towards mutualisation with some baby steps. We will probably make lots of mistakes (and we know you’ll point them out). Where we end up will depend as much on you as it does on us.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.