Several years ago now I was working with a team at Yahoo! who were building a platform that automatically surfaced relevant content for visitors to yahoo.com. The engineers were writing algorithms that intended to make the Internet more meaningful to people.

The team eventually worked their way into the Yahoo! home page experience. The Yahoo! home page can reorder content based on what the platform thinks you will most likely click on.

In a sort of similar way, the new Google Instant feature responds to your behaviors and adjusts as you give Google clues as to your intent.

In both cases, the computers help you work less to get what you want faster.

These kinds of innovations are a response to the growth rate of information on the Internet. The big dotcoms need to preserve their position in the market. And it will work to a degree, I’m sure, as the Yahoo!, Google and Facebook infrastructures get so sophisticated that they can’t be beaten at what they do.

But the network is changing shape, and I wonder if these companies are failing to actually evolve with people and the changes happening in society as a result of the presence of this new infrastructure in our world.

How did we arrive here?

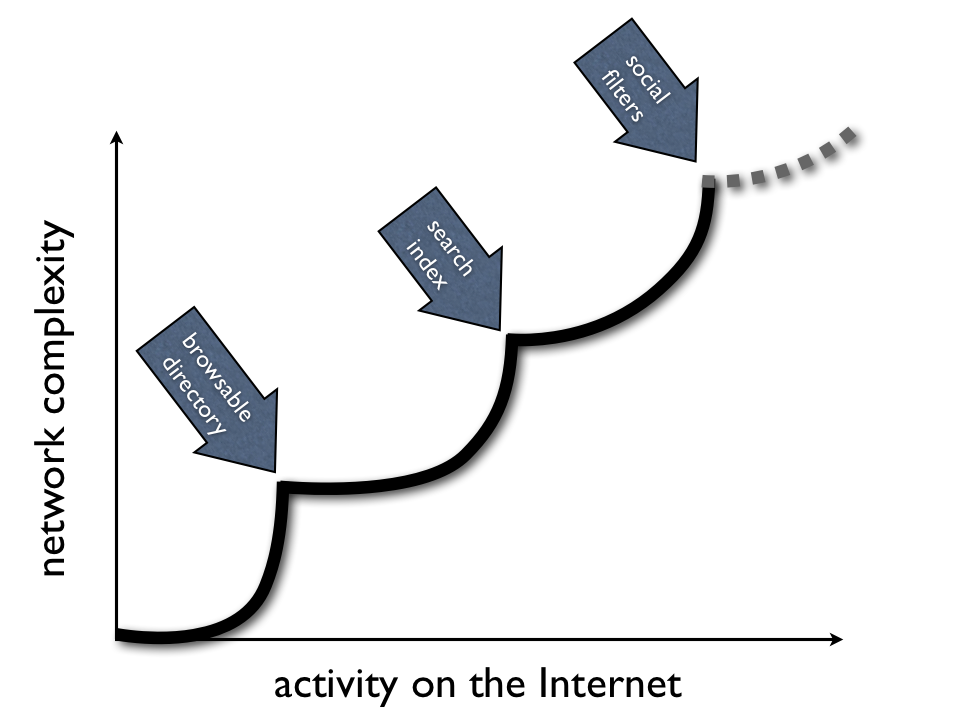

When the world of possibility gets lost in the volume of options people get frustrated. And when people get frustrated technology breakthroughs happen.

This chart shows how certain technological breakthroughs have made the Internet more manageable for people.

In the very early days of the web it was easy enough to find what you wanted just by hopping around from document to document. But it didn’t take long for the world of documents to explode. And when it exploded people became overwhelmed. When they became overwhelmed opportunity opened up to help people get started on their Internet journeys.

The directory took shape, and Yahoo! became the center of the web.

But the directory got full. There was no way to track everything as more and more people arrived and more and more organizations and individuals put more and more documents on the web. The volume of information went through another explosion, and people got frustrated again.

The search game followed, and Google became the center of all things web.

Now, of course, the search engine got full, too. In 2008, Google indexed over 1 trillion documents. The number of searches required to find what you wanted escalated and irritated people. And as the Internet population topped 1 billion people the amount of activity happening online made findability a madhouse again.

People coopted other people to make the Internet feel more human again. The social filter changed the balance of power in our relationship with shared knowledge, and information began to find us.

But this will change, too. Not only will more people join the party, but more networks will get connected and dump large piles of information onto the Internet, not just simple documents. And when real world devices flood the network the connected experience will become overwhelming yet again. Your friends won’t be good enough at helping you to manage your experience.

The new infrastructure

Tom Coates’ recent dConstruct presentation addresses some of this. He says lots of interesting things that anyone making a career developing for the Internet really should hear:

“The increase in transport infrastructure has completely transformed the way we make things and even what we can make….today the history of any object around you is a long and intricate chain of exchange, manufacture, component building, transport. Every object around you implicates the entire planet. Why isn’t the web like that?”

The networked world is still in its infancy, but the many ways we can interleave aspects of our lives with the people and things around us is absolutely incredible. The power people have in their hands is enormous when they know they have it, overwhelming when it discovers them.

With interesting raw data, useful APIs, connected devices and social triggers all around us now the materials to broker and assemble intelligent tools are getting cheaper and easier to offer people. We can devise algorithms that learn and automagically make the nodes on the network more accessible and relevant and valuable to each of us when and where we care about them.

But machines are not great at creating meaning, differentiating emotive responses, interpreting our motivations and contextualizing historical, personal and social references.

Wag the dog

The problem then surfaces when we assume that machines should be doing the hard work of making judgments about things. When machines make lots of small decisions on our behalf we become tempted to let them make the big decisions for us, too.

Amar Bhidé wrote an essay for Harvard Business Review titled “The Judgment Deficit“. He explains how the financial crisis was the result of our willingness to forgo important moral positions because we let machines interpret things humans should be looking at.

“A new form of centralized control has taken root—one that is the work not of old-fashioned autocrats, committees, or rule books but of statistical models and algorithms. These mechanistic decision-making technologies have value under certain circumstances, but when misused or overused they can be every bit as dysfunctional as a Muscovite politburo. Consider what has just happened in the financial sector: A host of lending officers used to make boots-on-the-ground, case-by-case examinations of borrowers’ creditworthiness. Unfortunately, those individuals were replaced by a small number of very similar statistical models created by financial wizards and disseminated by Wall Street firms, rating agencies, and government-sponsored mortgage lenders. This centralization and robotization of credit flourished as banks were freed from many regulatory limits on their activities and regulators embraced top-down, mechanistic capital requirements. The result was an epic financial crisis and the near-collapse of the global economy. Finance suffered from a judgment deficit, and all of us are paying the price.”

The financial meltdown could be interpreted as an autopilot problem, laziness as a result of efficiency. But perhaps even more important than economic catastrophe is the potential for cultural divides to sharpen and even turn violent when people fail to cooperate in healthy ways.

The existence of the network and the machines that make it do wonderful things does not change the fact that we are human, that we can be greedy, cruel, selfish, etc. The network will only amplify the best and worst about humanity.

Ethan Zuckerman woke me up to the important nuances of forming a global society via the Internet in his Activate Summit presentation this summer. The fact that we can communicate with individuals in far away countries, conduct transactions via phone, make goods in one place and ship them from another individually or en masse anywhere in the world does not mean that we understand the people we’re interacting with.

Fish oil, not snake oil

Enabling people to communicate with eachother around the world and to publish on the world’s stage is great. It’s hugely important. As is enabling and incentivizing organizations and institutions to release the raw data that drives what they do. And the many approaches to stitching these things together via infrastructure is a must-have for future generations, as Mr. Coates said.

But we must also learn how to step back and assess the value of the network, the connections happening within and across it. We must learn how to evaluate and articulate what changes need to happen to improve it and our relationship with it.

Without humanizing the decisions that are made as a result of the work computers are doing on our behalf we will be creating crutches for our brains and validating Nick Carr’s fears. Rather than help people take back control of their lives, the technologies will reinforce current power structures and enable new ones that hurt us.

When the next wave of activity on the network renders the social filter unmanageable the technology on the network should respond by empowering individuals and groups to better ourselves and improve global society rather than find more ways for us to do less.

When the next wave of activity on the network renders the social filter unmanageable the technology on the network should respond by empowering individuals and groups to better ourselves and improve global society rather than find more ways for us to do less.

There’s no need to create a new boss that looks just like the old boss. We can do better than that.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Activate 2010: Insights into the web (guardian.co.uk)

- Why the Web Went Wrong: From Self-Organized Swarms to Unruly Flash Mobs (gauravonomics.com)