Given the impressive rate of change happening in the digital market we have to consider how long this model will be relevant. Â Is it days, months, years, decades?

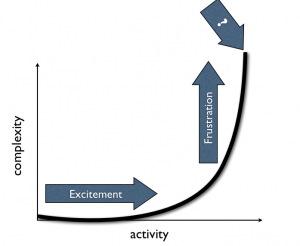

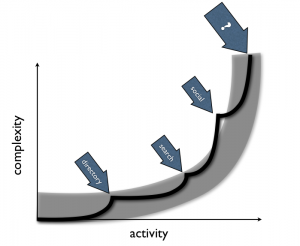

The repeating pattern in this market seems to be an exponential curve of exciting new activity that eventually results in overwhelming complexity. Â When the curve reaches a certain breaking point, instability reigns and new players suddenly enter the market.

John Battelle recently wrote about this idea in terms of “Signal, Curation, and Discovery.” Â He said:

“I have a new discovery problem: There’s simply too much content for me to grok. (For more on this, see Twitter’s Great Big Problem Is Its Massive Opportunity). Add in Facebook (people) and Google search (a proxy for everything on the web), and I’m overwhelmed by choices, all of them possibly good, but none of them ranked in a way that helps me determine which I should pay attention to, when, or why.

It’s 1999 all over again, and I’m not talking about a financing bubble. The ecosystem is ripe for another new player to emerge, and that’s one of the reasons I went to see the folks at Tumblr yesterday.”

Similarly, Amit Kapor of Gravity sees the pattern moving from ‘Their Web’ to ‘Our Web’ to ‘Your Web’ in a post called “The Future Will Be Personalized“:

“Once the web knows your interests, it can start to change… Any website or app can use knowledge of your interests in order to give you a personal experience.”

The new dominant players that break through during these unstable moments in the market seem to accomplish two things: 1) creating a new layer of activity that simplifies the complexity in the network, 2) commercializing access to or on top of that activity.

In the very early days of the web it was easy enough to find what you wanted just by clicking from page to page in your web browser. Â The web was a simple map of documents with hyperlinks.

But it didn’t take long for the number of documents on the web to explode.  Activity accelerated, and, as a result, soon the network became too complex.

The instability created opportunity which was captured in the form of a directory (among  other things).

What started literally as a list of links called Jerry and David’s Guide to the World Wide Web became Yahoo!, a directory that simplified the network for people.

The business model was very sensible. Â Yahoo! sold display ad units on their web pages which were relevant in the context of user’s actions…browsing for things.

By January 3, 2000 the company reached a market cap of $80 billion.

But the directory got full, and the Internet felt too big and complex again.

Then even Yahoo! couldn’t track everything being published on each web site across the whole network in a directory. Â More and more people arrived and more and more organizations and individuals published more and more documents.

The volume of information being published on the web went through another exponential growth curve. Â Too much activity resulted in too much complexity.

Google’s answer to simplifying the network won out by parachuting people directly into the page on a web site that had the information they wanted.  Of course, they also devised an ad platform to match people’s actions…ads targeted to those very specific search queries.

Subsequently, Google earned over $20 billion in revenue last year and currently have a market cap of $200 billion.

Activity across the network grew exponentially again.  In 2008, Google indexed over 1 trillion documents.  And, you know the story now, the increase in activity brought with it complexity.

Google began to struggle with maintaining a good search-to-result ratio, and the amount of activity happening online made findability a challenge again.

The next breakthrough to simplify the network came in the form of human filters.

People coopted other people to make the Internet feel more accessible again. Â The social filter changed the balance of power in our relationship with shared knowledge, and information felt like it began to find us.

Facebook and Twitter resolve this by reducing complexity and also benefitting from activity.

Just like its predecessors, Facebook has found ways to sell ads against these social filters by targeting ads in the context of people’s actions…sharing information.

Facebook will earn an estimated $2 billion in 2010 and has an estimated $50 billion market cap in secondary markets.

The social world has a lot of growth ahead of it, but this will change, too.

Not only will more people join the party, but more networks will get connected and dump large piles of information onto the Internet, not just simple documents. Â When more machines and devices flood the network including everything from phones to cars to household appliances the connected experience will become overwhelming and too complex yet again.

Your friends and family won’t be good enough at helping you to manage your experience.  The concept of a friend itself will get murky and overwhelm you with too many options.

We are now in yet another wave in the pattern, the exponential curve resulting from increasing activity online.

These waves appear to come in about 5 year increments, so it’s possible that the breakthroughs that will mark the end of this wave and the beginning of the next are either right in front of us today or just around the corner.

What kinds of breakthroughs will happen now?

I won’t answer definitively in part because I honestly don’t know but also because this is where invention happens.  Invention happens because humans solve problems with their own creativity, hard work and luck, not because markets predetermine what happens next.

On the other hand there are some healthy and very tangible conditions for change staring us in the face right now.

Smartphone apps, for example, are reducing the complexity of the network for people.  There’s a convenient business model for selling apps to people.  And the devices that distribute  apps are proliferating.

Smartphone makers shipped over 80 million smartphones worldwide in Q3 2010 which is actually up over 90% from a year ago.

Similarly, social activity online is changing the shape of the market.  The number of relationships we all have through all of our social apps and the amount of lifestream data we’re expected to catch is overwhelming.

Given the history of the network, it’s not likely that Facebook or Twitter are going to be able to solve the problem they are creating, just as Google and Yahoo! before them have so far failed to solve the problems they’ve created.

Might there be a pattern in the pattern?

Could it be that Yahoo!, Google and Facebook are all now contributing to a complexity problem in concert?  And, if so, then isn’t the next breakthrough one where the network itself is given a new lens through which to reduce the complexity that then benefits from activity?

Could the answer be about new visual languages and storytelling? Â reputation? Â hyper-distribution? Â data? Â all of the above?

…or perhaps even a total rejection of the network itself?

I would hate to see the anti-network movement prematurely subvert the potential of what is being accomplished today. Â But if it is an inevitable response to the network’s growth then I hope the characteristics of that movement are equally constructive and empowering.

Regardless, the trick to understanding meaning in the longer pattern whether its about language, devices, data, social activity, anti-networks or whatever is knowing your own context and where you want to go, what you want to be.

This series is an attempt to assemble some ideas I’ve been exploring for a while. Â Most of it is new, and some of it is from previous blog posts and recent-ish presentations. I’ve split the document up into a series of posts on the blog here, but it can also be downloaded in full as a PDF or viewed as a sort of ebook via Scribd: