The Internet platform business has some unique challenges. It’s very tempting to adopt known models to make sense of it, like the PC business, for example, and think of the Internet platform like an operating system.

The similarities are hard to deny, and who wouldn’t want to control the operating system of the Internet?

In 2005, Jason Kottke proposed a vision for the “WebOS” where users could control their experience with tools that leveraged a combination of local storage and a local server, networked services and rich clients.

“Applications developed for this hypothetical platform have some powerful advantages. Because they run in a Web browser, these applications are cross platform, just like Web apps such as Gmail, Basecamp, and Salesforce.com. You don’t need to be on a specific machine with a specific OS…you just need a browser + local Web server to access your favorite data and apps.”

Prior to that post, Nick Carr offered a view on the role of the browser that surely resonated with the OS perspective for the Internet:

“Forget the traditional user interface. The looming battle in the information technology business is over control of the utility interface…Control over the utility interface will provide an IT vendor with the kind of power that Microsoft has long held through its control of the PC user interface.”

He also responded later to Kottke’s vision saying that the reliance on local web and storage services on a user’s PC may be unnecessary:

“Your personal desktop, residing entirely on a distant server, will be easily accessible from any device wherever you go. Personal computing will have broken free of the personal computer.”

But the client layer is merely a piece of the much larger puzzle, in my opinon.

Dare Obasanjo more recently broke down the different ideas of what “Cloud OS” might mean:

“I think it is a good idea for people to have a clear idea of what they are talking about when they throw around terms like “cloud OS” or “cloud platform” so we don’t end up with another useless term like SOA which means a different thing to each person who talks about it. Below are the three main ideas people often identify as a “Web OS”, “cloud OS” or “cloud platform” and examples of companies executing on that vision.”

He defines them as follows:

- WIMP Desktop Environment Implemented as a Rich Internet Application (The YouOS Strategy)

- Platform for Building Web-based Applications (The Amazon Strategy)

- Web-based Applications and APIs for Integrating with Them (The Google Strategy)

The OS metaphor has lots of powerful implications for business models, as we’ve seen on the PC. The operating system in a PC controls all the connections from the application user experience through the filesystem down through the computer hardware itself out to the interaction with peripheral services. Being the omniscient hub makes the operating system a very effective taxman for every service in the stack. And from there, the revenue streams become very easy to enable and enforce.

But the OS metaphor implies a command-and-control dynamic that doesn’t really work in a global network controlled only by protocols.

Internet software and media businesses don’t have an equivilent choke point. There’s no single processor or function or service that controls the Internet experience. There’s no one technology or one company that owns distribution.

There are lots of stacks that do have choke points on the Internet. And there are choke points that have tremendous value and leverage. Some are built purely and intentionally on top of a distribution point such as the iPod on iTunes, for example.

But no single distribution center touches all the points in any stack. The Internet business is fundamentally made of data vectors, not operational stacks.

Jeremy Zawodny shed light on this concept for me using building construction analogies.

He noted that my building contractor doesn’t exclusively buy Makita or DeWalt or Ryobi tools, though some tools make more sense in bundles. He buys the tool that is best for the job and what he needs.

My contractor doesn’t employ plumbers, roofers and electricians himself. Rather he maintains a network of favorite providers who will serve different needs on different jobs.

He provides value to me as an experienced distribution and aggregation point, but I am not exclusively tied to using him for everything I want to do with my house, either.

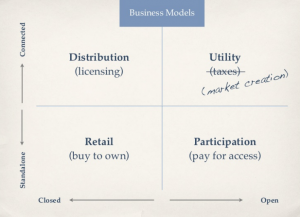

Similarly, the Internet market is a network of services. The trick to understanding what the business model looks like is figuring out how to open and connect services in ways that add value to the business.

In a precient viewpoint from 2002 about the Internet platform business, Tim O’Reilly explained why a company that has a large and valuable data store should open it up to the wider network:

“If they don’t ride the horse in the direction it’s going, it will run away from them. The companies that “grasp the nettle firmly” (as my English mother likes to say) will reap the benefits of greater control over their future than those who simply wait for events to overtake them.

There are a number of ways for a company to get benefits out of providing data to remote programmers:

Revenue. The brute force approach imposes costs both on the company whose data is being spidered and on the company doing the spidering. A simple API that makes the operation faster and more efficient is worth money. What’s more, it opens up whole new markets. Amazon-powered library catalogs anyone?

Branding. A company that provides data to remote programmers can request branding as a condition of the service.

Platform lock in. As Microsoft has demonstrated time and time again, a platform strategy beats an application strategy every time. Once you become part of the platform that other applications rely on, you are a key part of the computing infrastructure, and very difficult to dislodge. The companies that knowingly take their data assets and make them indispensable to developers will cement their role as a key part of the computing infrastructure.

Goodwill. Especially in the fast-moving high-tech industry, the “coolness” factor can make a huge difference both in attracting customers and in attracting the best staff.”

That doesn’t clearly translate into traditional business models necessarily, but if you look at key business breakthroughs in the past, the picture today becomes more clear.

- The first breakthrough business model was based around page views. The domain created an Apple-like controlled container. Exposure to eyeballs was sold by the thousands per domain. All the software and content was owned and operated by the domain owner, except the user’s browser. All you needed was to get and keep eyeballs on your domain.

- The second breakthrough business model emerged out of innovations in distribution. By building a powerful distribution center and direct connections with the user experience, advertising could be sold both where people began their online experiences and at the various independent domain stacks where they landed. Inventory beget spending beget redistribution beget inventory…it started to look a lot like network effects as it matured.

- The third breakthrough business model seems to be a riff on its predecessors and looks less and less like an operating system. The next breakthrough is network effects.

Network effects happen when the value of the entire network increases with each node added to the network. The telephone is the classic example, where every telephone becomes more valuable with each new phone in the network.

Network effects happen when the value of the entire network increases with each node added to the network. The telephone is the classic example, where every telephone becomes more valuable with each new phone in the network.

This is in contrast to TVs which don’t care or even notice if more TVs plug in.

Recommendation engines are the ultimate network effect lubricator. The more people shop at Amazon, the better their recommendation engine gets…which, in turn, helps people buy more stuff at Amazon.

Network effects are built around unique and useful nodes with transparent and highly accessible connection points. Social networks are a good example because they use a person’s profile as a node and a person’s email address as a connection point.

Network effects can be built around other things like keyword-tagged URLs (del.icio.us), shared photos (flickr), songs played (last.fm), news items about locations (outside.in).

The contribution of each data point wherever that may happen makes the aggregate pool more valuable. And as long as there are obvious and open ways for those data points to talk to each other and other systems, then network effects are enabled.

Launching successful network effect businesses is no easy task. The value a participant can extract from the network must be higher than the cost of adding a node in the network. The network’s purpose and its output must be indespensible to the node creators.

Massively distributed network effects require some unique characteristics to form. Value not only has to build with each new node, but the value of each node needs to increase as it gets leveraged in other ways in the network.

For example, my email address has become an enabler around the Internet. Every site that requires a login is going to capture my email address. And as I build a relationship with those sites, my email address becomes increasingly important to me. Not only is having an email address adding value to the entire network of email addresses, but the value of my email address increases for me with each service that is able to leverage my investment in my email address.

Then the core services built around my email address start to increase in value, too.

For example, when I turned on my iPhone and discovered that my Yahoo! Address Book was automatically cooked right in without any manual importing, I suddenly realized that my Yahoo! Address Book has been a constant in my life ever since I got my first Yahoo! email address back in the ’90’s. I haven’t kept it current, but it has followed me from job to job in a way that Outlook has never been able to do.

My Yahoo! Address Book is becoming more and more valuable to me. And my iPhone is more compelling because of my investment in my email address and my address book.

Now, if the network was an operating system, there would be taxes to pay. Apple would have to pay a tax for accessing my address book, and I would have to pay a tax to keep my address book at Yahoo!. Nobody wins in that scenario.

User data needs to be open and accessible in meaningful ways, and revenue needs to be built as a result of the effects of having open data rather than as a margin-based cost-control business.

But Dare Obasanjo insightfully exposes the flaw in reducing openness around identity to individual control alone:

“One of the bitter truths about “Web 2.0” is that your data isn’t all that interesting, our data on the other hand is very interesting…A lot of “Web 2.0″ websites provide value to their users via wisdom of the crowds appproaches such as tagging or recommendations which are simply not possible with a single user’s data set or with a small set of users.”

Clearly, one of the most successful revenue-driving opportunities in the networked economy is advertising. It makes sense that it would be since so many of the most powerful network effects are built on people’s profiles and their relationships with other people. No wonder advertisers can’t spend enough money online to reach their targets.

It will be interesting to see how some of the clever startups leveraging network effects such as Wesabe think about advertising.

Wesabe have built network effects around people’s spending behavior. As you track your finances and pull in your personal banking data, Wesabe makes loose connections between your transactions and other people who have made similar transactions. Each new person and each new transaction creates more value in the aggregate pool. You then discover other people who have advice about spending in ways that are highly relevant to you.

I’ve been a fan of Netflix for a long time now, but when Wesabe showed me that lots of Netflix customers were switching to Blockbuster, I had to investigate and before long decided to switch, too. Wesabe knew to advise me based on my purchasing behavior which is a much stronger indicator of my interests than my reading behavior.

Advertisers should be drooling at the prospects of reaching people on Wesabe. No doubt Netflix should encourage their loyal subscribers to use Wesabe, too.

The many explicit clues about my interests I leave around the Internet — my listening behavior at last.fm, my information needs I express in del.icio.us, my address book relationships, my purchasing behavior in Wesabe — are all incredibly fruitful data points that advertisers want access to.

And with managed distribution, a powerful ad platform could form around these explicit behaviors that can be loosely connected everywhere I go.

Netflix could automatically find me while I’m reading a movie review on a friend’s blog or even at The New York Times and offer me a discount to re-subscribe. I’m sure they would love to pay lots of money for an ad that was so precisely targeted.

That blogger and The New York Times would be happy share revenue back to the ad platform provider who enabled such precise targeting that resulted in higher payouts overall.

And I might actually come back to Netflix if I saw that ad. Who knows, I might even start paying more attention to ads if they started to find me rather than interrupt me.

This is why the Internet looks less and less like an operating system to me. Network effects look different to me in the way people participate in them and extract value from them, the way data and technologies connect to them, and the way markets and revenue streams build off of them.

Operating systems are about command-and-control distribution points, whereas network effects are about joining vectors to create leverage.

I know little about the mathematical nuances of chaos theory, but it offers some relevant philosophical approaches to understanding what network effects are about. Wikipedia addresses how chaos theory affects organizational development:

“Most of the focus on chaos theory is primarily rooted in the underlying patterns found in an otherwise chaotic enviornment, more specifically, concepts such as self-organization, bifurcation and self-similarity…

Self-organization, as opposed to natural or social selection, is a dynamic change within the organization where system changes are made by recalculating, re-inventing and modifying its structure in order to adapt, survive, grow and develop. Self-organization is the result of re-invention and creative adaptation due to the introduction of, or being in a constant state of, perturbed equilibrium.”

Yes, my PC is often in a state of ‘perturbed equilibrium’ but not because it wants to be.

There must be kitchen design experts around the world I can learn from. Equally, I’m sure there is a guy around the corner from me who can give me some tips on local services. Will Architectural Digest or Home & Garden connect me to these different people? No. Will The San Francisco Chronicle connect us? No.

There must be kitchen design experts around the world I can learn from. Equally, I’m sure there is a guy around the corner from me who can give me some tips on local services. Will Architectural Digest or Home & Garden connect me to these different people? No. Will The San Francisco Chronicle connect us? No.